Craig Venter, the Man Who Knew Himself

https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/science/bioscience/what-happened-to-our-genomes/Biology |

DNA |

Genetics |

Leading Figures |

ResearchVentana al Conocimiento (Knowledge Window)Scientific journalism

Time 4 to read

It’s not very usual for biologists to own luxury yachts almost 30 metres long, and for those who have them, it’s not common to dedicate them to collecting samples of marine microbes with a view to having their genomes sequenced. But John Craig Venter (Salt Lake City, USA, October 14, 1946) is not your usual biologist. When in 2004 he undertook a scientific expedition around the world aboard his sailboat Sorcerer II, he didn’t do so to emulate Charles Darwin in the HMS Beagle, but rather to surpass him, to “contextualize everything that Darwin missed,” according to what Venter told

Wired in 2004. And maybe this example serves to illustrate what it is that some praise and others criticize in the scientist and entrepreneur who is currently turning 70: ambitions so lofty they can only be reached on the stilts of an equally elevated ego.

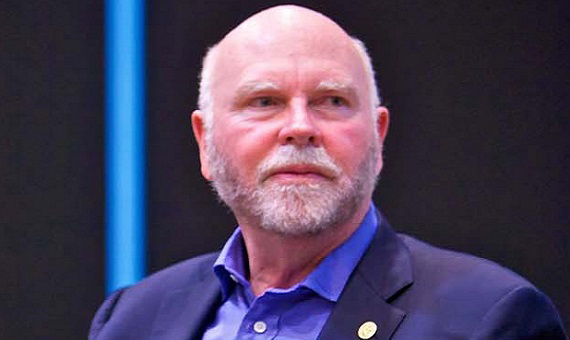

Craig Venter, biologist and entrepreneur from Synthetic Genomic, in 2011. Credit: Mauricio Ramirez, Chemical Heritage Foundation.

Rebellion is not normally the inheritance of the intelligent, but perhaps intelligence is the salvation of the rebellious. For Venter, his IQ of 142 allowed him to spend more time surfing than studying during his childhood in California, without fear of harming his future. And being drafted into a war –the one in Vietnam– which he opposed, allowed him to voluntarily choose his role in it, that of health. From those terrible years at the University of Death, as he defined it in his autobiography A Life Decoded (Viking, 2007), comes the story of a suicide attempt by swimming out to sea, a story that feeds his legend.

Venter began to earn a reputation as the bad boy of molecular biology during his initial period at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). While there, he perfected a technique called Expressed Sequence Tags (EST) that has since been employed by thousands of researchers around the world, and which allows them to obtain and store copies for study of all the active genes in a cell.That first achievement revealed the direction that Venter’s career would follow – the application of groundbreaking techniques, often already existing but underused, that propel great leaps forward at the frontiers of biology. But it was also his first scandal when it was learned that Venter and the NIH were attempting to patent the genes identified by the EST.

VENTER VS. THE DISCOVERER OF DNA

While the protests ruined the aspiration to patent genes, Venter became embroiled in a new dispute with the scientific establishment when the technique that he proposed for the Human Genome Project was rejected. Instead of trying to sequence long DNA strands of chromosomes by moving over them gingerly, step by step, as had hitherto been done, Venter proposed a more explosive option: smashing the genome into countless small pieces and sending them into the air, reading them, and then letting computers glue the pieces of the vase back together.

James Watson, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, dismissed the technique, suggesting that it belonged to monkeys.

Venter (right) with Barry Schuler, former AOL CEO, in his yacht. Credit: Steve Jurvetson.

Clearly, Venter did not try to be particularly cordial. When he founded the company Celera Genomics to sequence the human genome on its own, thereby competing with the public project, he recommended that those responsible for the latter should devote their efforts to another organism, more specifically, the mouse. It is said that Watson came to compare him to Hitler, but Venter’s ego and ambition had solid foundations. The shotgun sequencing technique, which he did not invent but rather optimized, managed to finish the race to map the human genome at the same time as the public project, but the latter was forced to redouble its efforts so as not to be defeated by the uncomfortable competition from Venter.

Venter’s victory opened the door to everything else: public notoriety, respect from his colleagues, a place on the lists of the most influential people, new businesses, money and, of course, the yacht. The Global Ocean Sampling Expedition, completed in 2006, was one more piece in the grand scheme that Venter is currently working on. Sequencing the biodiversity of the oceans is itself a target of Darwinian proportions; however, it is not the final goal, but rather a milestone that extends the catalogue of microbes available to be converted into the factories of the future: modified microorganisms that produce drugs or fuel, or are responsible for collecting the garbage that we spread around the planet.

OBJECTIVE: CREATE SYNTHETIC LIFE

But beyond the customized microbes, there is still a higher purpose: Venter yearns to become the first human to create synthetic life. This was described in his book: “I want to move away from the coast into uncharted waters, into a new phase of evolution, the day when one species based on DNA can sit in front of a computer to design another.” In March 2016,

he published his latest conquest to date, creating a minimal synthetic genome able to operate a cell with only 473 genes.

In person, Venter seems affable, though distant. His apparent attempt to be pleasant produces the feeling of hiding a hint of coldness, which is revealed when he reacts harshly to questions with intent, those that a journalist is required to ask. But without doubt Venter knows that it is not only science that interests him. At the end of the day, he wanted it this way: Venter did not bequeath to humanity just any genome, but his own genome.

As if following the conventions in the “know thyself” field, his autobiography is sprinkled with annotations explaining aspects of his life and personality from the perspective of his genes. “I want to find out if a decoded life is really a life understood,” he wrote. “New interpretations of Craig Venter, based on my DNA, will continue to be made long after life has left my body. I have no other choice but to leave the ultimate interpretation to the reader and to History.” Like that, with a capital H.By Javier Yanes for Ventana al Conocimiento

What Happened to our Genomes?

Want to have your own complete genome? No problem. Write down the steps you must follow: first, get the support of a doctor; you still cannot request this service, at least not from a reliable supplier, without the approval of a physician who must sign the application. Then you have to

register online at

Understand your Genome from the California company,

Illumina. Once you have paid the fee of $4,900 (about €4,150), your doctor will receive by courier a kit for the extraction of samples, which must then be returned to the sender with a few drops of your blood. Illumina will send the results to your doctor and you will be invited to a symposium at which they will explain your genome in great detail. The price does not include travel costs, but at least you will receive an iPad mini with the

MyGenome app from Illumina that will reveal all the secrets of your DNA.

This is the closest we can currently get to that promise at the start of the century, that in a few years we would have our genome at our disposal for less than $1,000, about €850.

We are still far from being able to pop down to the pharmacy, throw a few coins into a machine and upload our DNA code directly onto our smartphone. But considering that the first human genome sequence was only completed in 2003, and that its obtention cost about three billion dollars, progress in the last decade cannot be described as anything less than meteoric.

The Human Genome Project was conducted with technology from the 1970s. This titanic initiative prompted many entrepreneurial scientists to develop new techniques of DNA sequencing, which has led us in just over ten years to already having more than 200,000 human genomes. Today

Illumina monopolizes 70% of the market, with its machines producing

90% of all genomes sequenced in the world. According to the biotechnologist and Swiss geneticist Glynne Ivo Gut, director of the

National Genome Analysis Centre of Spain, “Illumina is now the most viable sequencing platform.” The rest of the pie is divided among companies like 454 Life Sciences (Roche), Life Technologies or Pacific Biosciences. A year ago, on January 14, 2014,

Illumina announced it had reached the milestone of $1,000 per genome with its new platform HiSeq X Ten. Gut confirms that “in a research context, nowadays you can sequence a human genome with Illumina at a cost of $1,000.”

For those for whom this price is unaffordable, it is possible to freely join any of the research projects that recruit volunteers willing to donate some of their DNA to science. However, despite the spectacular advances, we still cannot freely exercise the right to own our own genome without the intervention of a professional, and our family doctor is still unable to access our genetic data to identify risks recorded in our DNA and advise us according to our profile. Why not?

In the opinion of Gut, the obstacles are not technological: “Technically, we would be able to introduce genomic sequencing into the clinical routine,” he assesses. “However, there are many questions of detail that must be resolved before it can be implemented on a large scale, both practical and organizational, legal and social.” These aspects that exceed the purely scientific are due to the fact that, in some cases, technology has advanced faster than regulations.Although the genetic data of each of us are presumably inviolable, there are still fears that its popularity could lead to abuses such as genetic discrimination. As well, one must keep in mind that the genetic profile of someone not only affects the individual but also their families; maybe someone wants to know the likelihood of their developing an incurable illness, but perhaps some relative of theirs prefers not knowing who shares that risk.

Moreover, and although it is now possible to read the entire DNA of a person, it is not so simple to standardize the process so that it can be reproduced in whatever centre. Recently Gut co-led a study,

pre-published on the website bioRxiv, where five institutes from different countries sequenced the same two samples, one a tumor and the other healthy, and the results did not all agree. “We must still define standards, standardize procedures and implement them,” says Gut.

Finally, there is still another challenge, that of interpreting the vast amount of data contained in a genome. It is a process that no longer depends on tubes and pipettes, but rather on computer systems, and it is as expensive as it is complex. “A human genome of clinical grade will require a major investment,” said Gut, for whom the jump to the hospital or the consulting room depends primarily on the tools capable of integrating genomic information in the healthcare process: “They must develop support systems for decision- making that prioritize the most relevant data for the doctor, quickly and reliably.”

在生物學界,有一個人無論做出多么離經叛道的事情,大家都不會感到驚奇。他素來以“科學怪人”(Bad boy of Science)聞名,他就是John Craig Venter。

他作為有史以來最最瘋狂的科學家,不僅擁有著無與倫比的意志和決心,也擁有著單挑整個世界不落下風的勇氣和能力,可以說是毀譽參半。

如今站在生命科學研究領域之巔的Venter怎么也不會想到,曾經的尋死少年,后來會一躍成為無人不知的“人造生命之父”。

1 學渣的逆襲

1946年,Venter出生于美國鹽湖城。因著骨子里的不安分基因,年少時的他頑劣異常。雖還說不上是個“壞小子”,但很像一匹性情暴躁的生馬駒,橫沖直撞地不守規矩。他癡迷于一切具有冒險意味的運動,航海、騎摩托、開賽車等都是他的心頭好。

因此,Venter自然不甘愿在教室里久坐。在他眼中,學習無疑是件乏味枯燥的事情,因而對學習也是從不上心。

童年期的Venter

在加州念中學時,他可是個名副其實的“學渣”。他的成績單似乎成為了A和B的絕緣體,一眼望去,幾乎全是C和D。

渾渾噩噩地混畢業后,Venter因著出色的游泳天賦(曾破過學校的游泳記錄),而被亞利桑那州立大學看中。

但厭倦了循規蹈矩生活的Venter,一口回絕了這份邀請。畢竟,對他而言,學習哪有喝酒、沖浪、泡妞的瀟灑生活來得自在痛快!

然而,好景不長,1967年越南戰爭的爆發,終是給這份愜意的生活畫了個句點。Venter應征入伍,并在新兵智力測試中獲得最高分。

這份碾壓所有新兵的高智商讓他有了選擇兵種的權利,Venter決定進入海軍醫院成為一名醫護兵。

在越南戰場服役期間的Venter(左一)

在越南戰場上,Venter第一回直面觸目驚心的生死場面,看著很多戰友搶救無效在他面前忍痛而去,他一度承受不了巨大的壓力而企圖自殺。

為了能葬身于大海之中,Venter他頭也不回地游向深海,卻意外碰上一群鯊魚。而當一條鯊魚,試探著撞他的時候,他本能地掙扎以求逃生。

這一瞬間,Venter意識到生命是何其的脆弱,又是何其的珍貴;而現有的醫療知識和技術又是如此匱乏,他感到自己不能再浪費時間了。

于是退役后,他決定要重修學業。天資聰慧的Venter在美國社區大學獲得全A成績后,順利進入了加州大學圣地亞哥分校,1972年獲得了生物化學本科學位,而后又花了僅僅三年時間榮獲了生理學、藥學博士學位。

2 科研路上鋒芒畢露,叫板六國科學家

1984年,Venter加入美國國家衛生研究院(NIH),成為一名科研人員。當時,正是分子生物學風起云涌的時代,牛人Waston 和Crick在1953年對DNA雙螺旋結構的解讀為大家指明了科研的主攻方向——解碼生命。

于是由美國NIH主導的人類基因組計劃(HGP)在1990年正式啟動。美、英、法、德、日和中國等6個國家的頂級科學家共同參與了這項預計耗資30億美元的人類基因“曼哈頓計劃”。

依據當時的設想,HGP需花費長達15年的時間才能完成,即在2005年,將人體內約10萬個基因的密碼全部解開,同時繪制出人類基因圖譜。

而在實際的執行過程中,HGP的測序卻舉步維艱。盡管投入該計劃的人力物力是當時的頂級配置,但是人數一多,機構臃腫、行動緩慢等缺點就顯示出來了。

1997年,在耗費了巨額資金和一半預定時間后,多國合作小組僅完成了3%的測序工作。如此龜速,Venter自然是看不下去的。

他認為,依照Sanger測序法(一代測序法),HGP是決計不會按時完成的!HGP需要一種全新的基因測序技術來進行測序工作!

將基因分割為1000bp有重疊序列的片段,而后通過加入鏈終止核苷酸,將一條DNA上的幾千萬甚至上億個堿基對一個一個測出來。

隨后,Venter提出一種天才想法:就是將DNA隨機打斷,而后像搭積木一樣通過接頭拼裝起來,即鳥槍法(霰彈槍測序法)的雛形。如果這個想法可行,那么測序速度必然是驚人的。

可如此提議卻遭到了NIH等專家的一致反對,畢竟國家隊是一向以“寧穩妥,勿遺憾”為原則的。

在國家隊看來,Sanger測序法可將測序錯誤的組合風險降至最低,可以保證產出最高質量的人類基因組序列結果;而鳥槍法中高度重復序列(如染色體的端粒和著絲點)會導致程序計算出錯,完全是一種有勇無謀的策略。

自此,Venter與國家隊徹底分道揚鑣。因堅信鳥槍法才是最高效的測序方法,離開NIH的他決定單干,并決定獨立完成人類基因組計劃。

他在市場上四處游說,宣稱只要給他投資實驗,他就能利用檢測出來的基因申請專利,將來就可以拿到高昂的專利費。

因而,1998年5月,在PerkinElmer公司3.3億美元 (僅是國際計劃的1/10) 的投資下,Venter又建立了名為Celera Genomics的私立公司,正式開始自己的人類基因組計劃。

Venter狂妄地放話道,要在3年內完成人類基因組的序列測定,還會為測出的基因申請專利保護。

國家隊的科研者們雖對此等狂言表示懷疑,但毫無疑問,在感受到來自于Venter的壓力后,他們也開始了“瘋狂”的測序行動。一場無聲的較量就此展開。

一邊是全球頂級科學家聯盟,一邊是科學“個體戶”的單打獨斗,怎么看都是Venter毫無勝算,可是誰也不會料到成功的天平會逐漸倒向后者。

鳥槍法的快速,結合后續所研發出的可提高準確性的計算機拼接新算法,Venter領導的科研小組先后完成了一個又一個的突破。

如單細胞生物流感嗜血桿菌(Haemophilus influenzae Rd)、具有最小基因組的單細胞生物生殖支原體(Mycoplasma genitalium)以及詹氏甲烷球菌(Methanococcus jannaschii)的全基因組測定。

如此看來,Venter是真的走到了HGP的前面。這樣成果,讓全世界愕然感嘆!Venter“申請基因專利”的蓬勃野心,也讓科學家們陷入恐慌!

畢竟,多國之所以合作進行HGP就是為了給全人類服務,而Venter的研究卻是企圖獨占人類基因資源,目的是贏利。

一時間,“科學狂人”、“像希特勒想要獨占世界一樣獨占人類基因組”和“生物壞小子”等不同惡名一起向他砸來......

而為了阻止人類基因組專利落入Venter一人之手,時任美國總統克林頓和英國首相布萊爾不得不聯合發表聲明人類基因組數據不允許專利保護,且必須對所有研究者公開,這才使得人類基因組圖譜這一全人類的財富沒有變成私有。

許是“國家利益至上”的勸諫生效,在克林頓總統的撮合下,不情愿的Venter只能加入國際基因測序聯盟,并同意將測得的數據上傳到數據庫,提供免費下載。

總統克林頓與Venter

Venter加入后,僅花費了3年時間,人類基因組計劃就完成了90%的基因測定。2000年6月,原定于2005年完成的人類基因組計劃基因草圖完成。

2001年2月國際人類基因組測序聯盟和Venter在Celera公司的研究團隊的人類基因組工作草圖的具體序列信息、測序方法以及序列的分析結果分別發表于Nature與Science雜志。

Venter和人類基因組研究所所長Francis Collins一起分享了當年A&E Network頒發的生物年度獎 (Biography of the Year),Venter本人更是被評選為“千禧年年度科學家”。

Collins和Venter一起登上Time雜志封面

然而,一夜成名的Venter并沒有風光多久,因沒有申請到基因專利,無法實現對Celera公司的承諾,致使公司運營出現困難,于是Venter于2002年被公司開除。

3 創造“人造生命”,彰顯征服世界的野心

這之后,Venter并沒有消沉太久。還不到3個月,執著的Venter便重回科研之路,用從Celera拿到的1 億多美元成立了用于基因領域研究的非營利性研究所,并聚攏了一批和他一樣才華橫溢、具有反叛精神的年輕科學家,很快他們便向世界宣告新理想——創造新的生命形式。

人們原以為會很快就會再次聽到一些石破天驚的消息時,卻沒想到隨后的8年中,Venter和他的實驗室既不發布消息也不接受采訪,只顧悶頭研究,一下子就淡出人們的視線。

這8年時間,似乎足以讓人遺忘這位桀驁不馴的科研狂人。但當2010年,Synthia(辛西婭)頂著“人造生命”的光環進入人們的視野時,整個世界沸騰了。

畢竟,自分子克隆技術問世后,這還是科學家們首次扮演上帝的角色,構造出從未存在過的生命形式——Synthia是首個完全由人造基因指令控制的生物。

然而,Synthia既無法欣賞自己的名字,也意識不到自己所帶給人類的震撼:因為它是一種細菌。

Venter研究團隊以絲狀支原體(Mycoplasma mycoides)的基因組為模板,從中抽絲剝繭提煉出生命的基石——必需基因、非必需基因和半必需基因,而后化學合成出一整套支原體的基因組,并將它移植到除去了DNA的山羊支原體(Mycoplasma capricolum)細胞內。而這套人工合成的基因組最終指導它所在的細胞活了下來。

Synthia的誕生并不容易:1078條DNA片段分布組合成一條長達1078809bp的人工基因組

此外,第一代Synthia身上的還另有獨特之處:Venter團隊特意為其設置了“個性簽名”,在細胞內注入一列“水印” DNA——嵌入了46個參與研究的科學家名字、三句名言以及一個密碼。

名言中的一句是:“去活著,去犯錯,去跌倒,去勝利,去從生命中創造新生命。”而密碼則是一個網址,解碼以后可以給他們發郵件。

人工合成細胞辛西婭

當然,對于Venter而言,Synthia不能止步于此,它的誕生只是Synthia1.0(>百萬bp,901個基因)而已,后續還需向Synthia2.0邁進。

Venter研究團隊持續發力,不斷刪減著非必需基因,優化著Synthia的基因組,終是讓Synthia2.0成為了擁有最小基因組的(576kbp,512個基因)、可以自行繁殖的細胞。

他們甚至還在Synthia2.0的基礎上,成功獲得了一個僅僅含有473個基因,基因組大小為531kbp的JCVI-syn3.0。

顯微鏡下的Syn1.0與Syn3.0。相比于“獨立”的Syn1.0,Syn3.0更傾向于“抱團”。

毫無疑問,Venter的研究引起了極大爭議,大多數人認為他是在“扮演上帝的角色,在褻瀆生命”,甚至還有人叫囂著要將文特爾趕出科學界,說他不配做科學家。

但這個飽受爭議的“科學狂人”只是一笑置之,繼續前行,并期望在以后能像搭積木一樣搭建出更多屬于自己的細胞。

他以一人之力單挑6國科學家,首創人造生命,締造生物界醫學傳奇